The First 90 Days by Michael Watkins

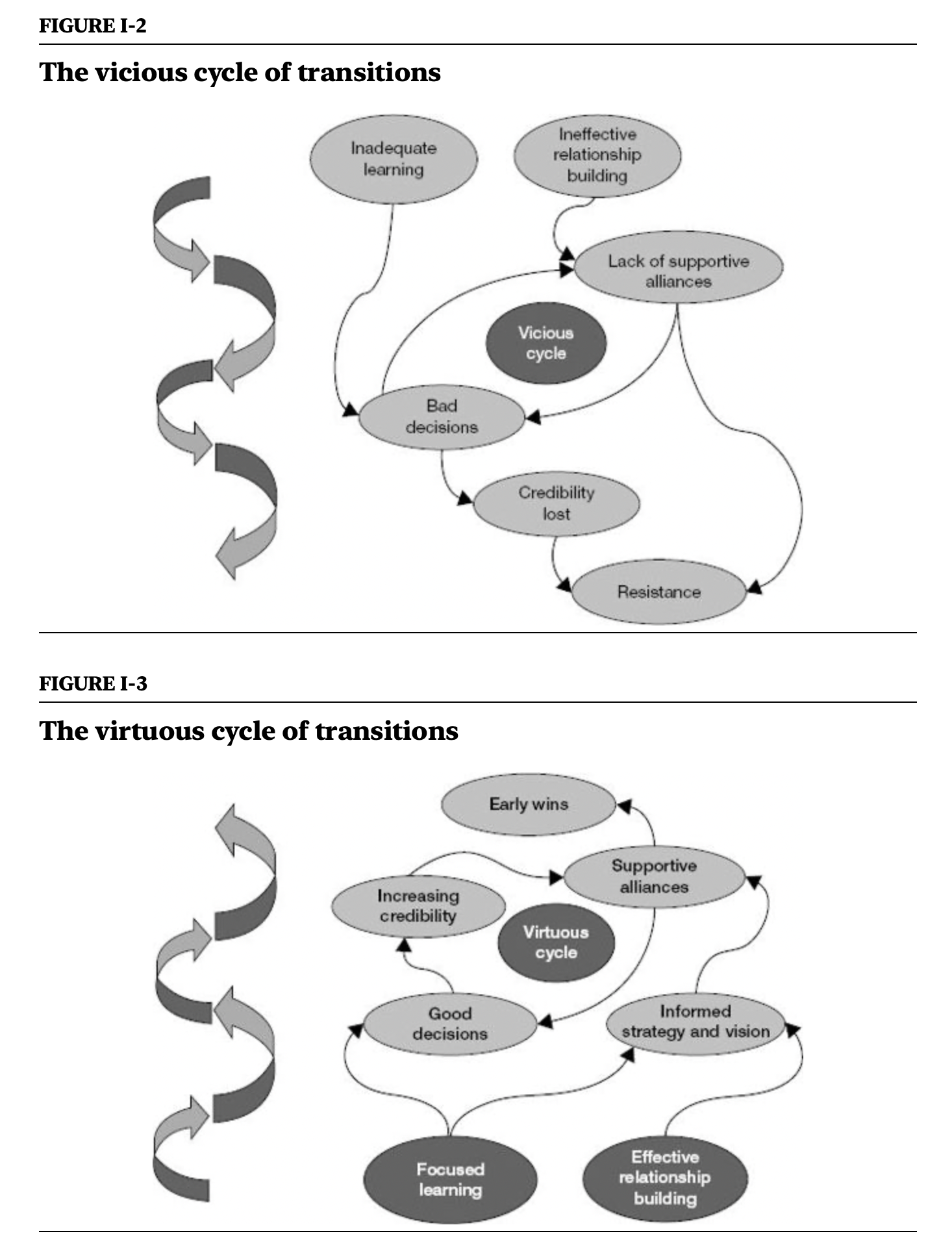

Transitions and career changes can be difficult to traverse. Building new relationships and learning about different domains and technologies requires a lot of time and effort. Additionally there is a limited period of time for a manager to prove themselves and early missteps can lead to a downward spiral.

Many firms integrate 30/60/90 days plans into their processes but they’re typically directed towards individual contributors. Managers, however, have a more complex role. In previous posts, I referenced how Will Larson describes various teams states and explains that managers have to apply different fixes depending on the state of the team. Similarly Daniel Goleman expounds on 6 different leadership styles for different types of teams. It’s clear that crafting a 30/60/90 day plan for a manager is contextual to the needs of the business. The challenge is it takes a lot of time and effort to gather context. How does one transition themselves towards successs?

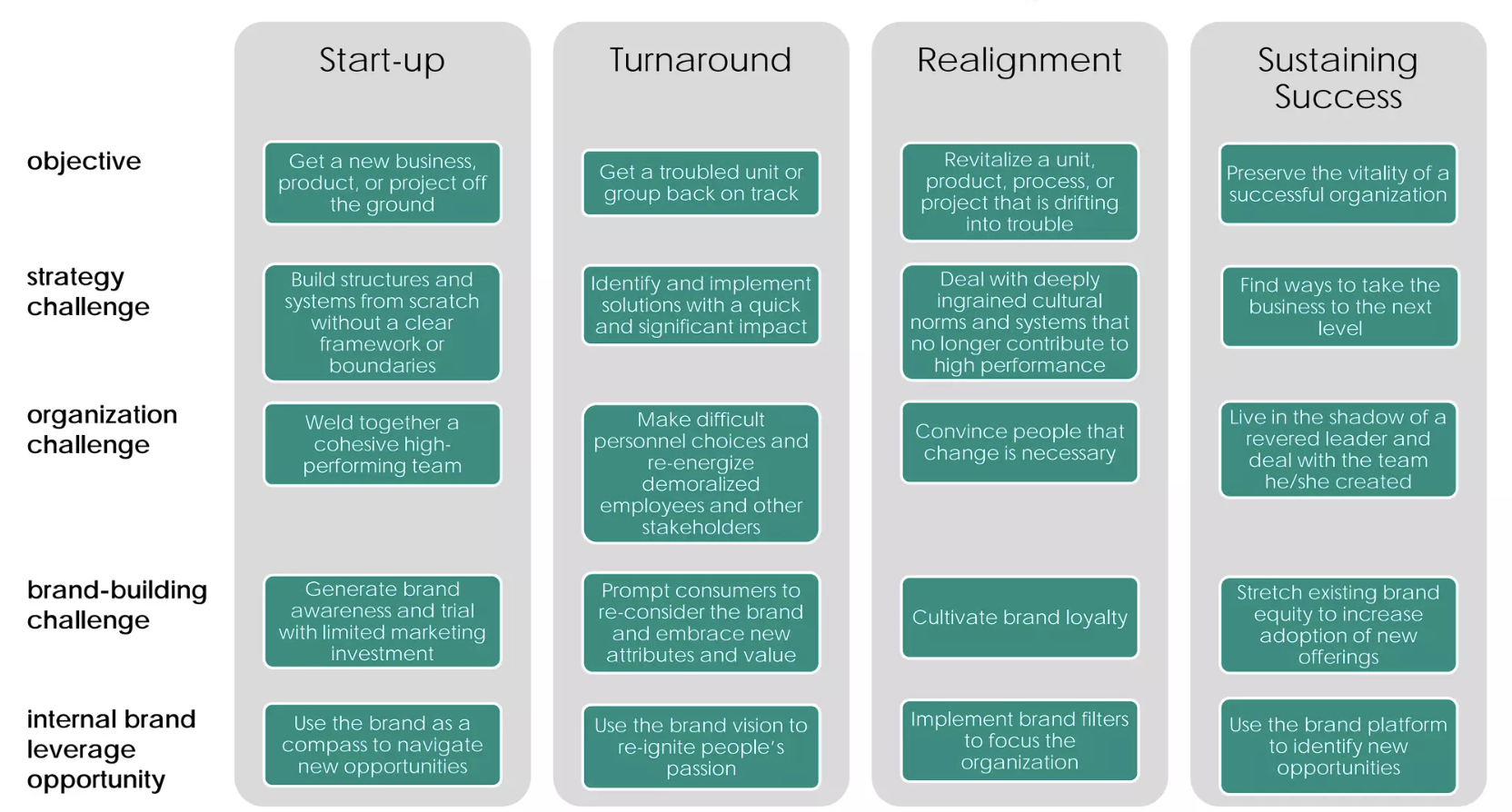

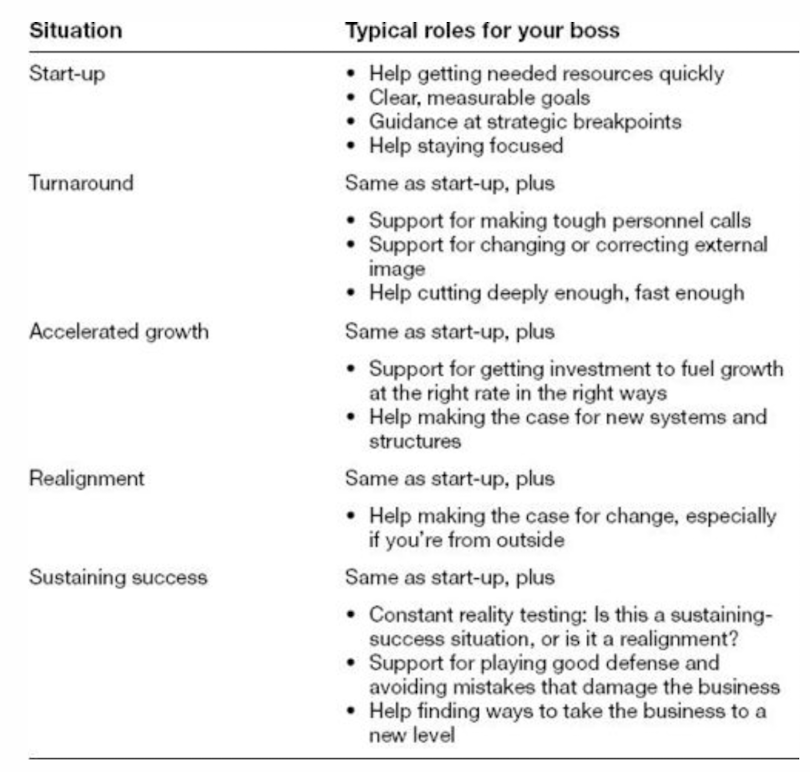

Watkins proposes a fundamental principles to enable successful transitions for new employees. Many of these mirror Goleman’s observations, for example, to not assume that what worked in a past role will work again. He also explains that different business states requires different leadership approaches (startup vs turnaround vs accelerated growth vs realignment vs sustaining success). Watkins recommends to avoid implementing massive changes right out of the gate (apart from turnaround). He also discusses SWOT analysis and provides tips to create a compelling vision to motivate the team.

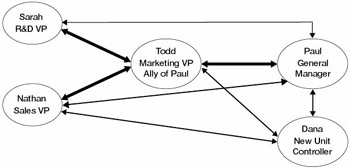

Watkins provides a practical viewpoint towards corporate culture, exhorting managers to build influence vertically but also horizontally with peers. He states that it is useful to map out spheres of influence and deciphering “hidden politics” within an organization in order to build support for proposals. Securing early wins is critical but these should ladder up to a long term goal rather than low hanging fruit.

Most illuminating to me were conversations to align your manager. It’s advantageous to be proactive and to take full ownership of building a new relationship and negotiating success within the first 90 days. Very early in my career, I fell into some of these traps, for example, not making an effort to schedule in-person time or long periods without contact. People I know have similarly fallen into traps, for example, expecting their managers to adapt to their styles instead of the other way round.

I would highly recommend managers to read and reflect on their transition journeys while reading this book. I have taken down some notes from my reading that were thought provoking and hope that you enjoy them too.

Book summary

Intro

- If you’re successful in building credibility and securing early wins, the momentum likely will propel you through the rest of your tenure. But if you dig yourself into a hole early on, you will face an uphill battle from that point forward.

- Your goal in every transition is to get as rapidly as possible to the break-even point. This is the point at which you have contributed as much value to your new organization as you have consumed from it.

- Common traps

- Sticking with what you know.

- Coming in with “the” answer.

- Fundamental principles

- Prepare yourself: Don’t stick to what you know.

- Accelerate your learning: Understand the business but also the politics.

- Match strategy to the situation.

- Secure early wins.

- Negotiate success. Because no other single relationship is more important, you need to figure out how to build a productive working relationship with your new boss (or bosses) and manage her expectations. This means carefully planning for a series of critical conversations about the situation, expectations, working style, resources, and your personal development. Crucially, it means developing and gaining consensus on your 90-day plan.

- Achieve alignment.

- Build your team.

- Create coalitions. Your success depends on your ability to influence people outside your direct line of control. Supportive alliances, both internal and external, are necessary if you are to achieve your goals. You therefore should start right away to identify those whose support is essential for your success, and to figure out how to line them up on your side.

- Keep your balance.

- Accelerate everyone.

Chapter 1: Prepare yourself

- It’s a mistake to believe that you will be successful in your new job by continuing to do what you did in your previous job, only more so.

- To preapre,identify the types of transitions you’re experiencing.

Getting promoted

- You need to learn to strike the right balance between keeping the wide view and drilling down into the details.

- No matter where you land, the keys to effective delegation remain much the same: you build a team of competent people whom you trust, you establish goals and metrics to monitor their progress, you translate higher-level goals into specific responsibilities for your direct reports, and you reinforce them through process.

- Decision making becomes more political—less about authority, and more about influence. That isn’t good or bad; it’s simply inevitable.

- There are two major reasons this is so. First, the issues you’re dealing with become much more complex and ambiguous when you move up a level—and your ability to identify “right” answers based solely on data and analysis declines correspondingly. Decisions are shaped more by others’ expert judgments and who trusts whom, as well as by networks of mutual support.

- Second, at a higher level of the organization, the other players are more capable and have stronger egos. Remember, you were promoted because you are able and driven; the same is true for everyone around you. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the decision-making game becomes much more bruising and politically charged the higher up you go. It’s critical, then, for you to become more effective at building and sustaining alliances.

- You need to establish new communication channels to stay connected with what is happening where the action is.

- One inescapable reality of promotion is that you attract much more attention and a higher level of scrutiny than before. You become the lead actor in a crucial public play. Private moments become fewer, and there is mounting pressure to exhibit the right kind of leadership presence at all times.

Onboarding to a new company

- Joining a new company is akin to an organ transplant—and you’re the new organ. If you’re not thoughtful in adapting to the new situation, you could end up being attacked by the organizational immune system and rejected.

- To overcome these barriers and succeed in joining a new company, you should focus on four pillars of effective onboarding: business orientation, stakeholder connection, alignment of expectations, and cultural adaptation.

- No matter how well you think you understand what you’re expected to do, be sure to check and recheck expectations once you formally join your new organization.

- Influence. Does the organization operate according to consensus, where the ability to persuade is key? These elements of the culture are often invisible and can take time to become clear.

- Execution. When it comes time to get things done, which matters more—a deep understanding of processes or knowing the right people?

- The challenges of entering new cultures arise not only when new leaders are transitioning between two different companies, but also when they move between units.

- You need to discipline yourself to devote time to critical activities that you do not enjoy and that may not come naturally. Beyond that, actively search out people in your organization whose skills are sharp in these areas, so that they can serve as a backstop for you and you can learn from them.

- Relearning how to learn can be stressful. So if you find yourself waking up in a cold sweat, take comfort. Most new leaders experience the same feelings. And if you embrace the need to learn, you can surmount them.

Chapter 2: Accelerate your learning

- The first task in making a successful transition is to accelerate your learning.

- A baseline question you always should ask is, “How did we get to this point?”

- Remember: simply displaying a genuine desire to learn and understand translates into increased credibility and influence.

- If you habitually find yourself too anxious or too busy to devote time to learning, you may suffer from the action imperative (compulsive need to take action). It is a serious affliction, because often, being too busy to learn results in a death spiral.

- Learning agenda.

- Questions about the past.

- How has this organization performed in the past? How do people in the organization think it has performed?

- What efforts have been made to change the organization? What happened?

- Questions about the present.

- Current vision.

- Who is capable?

- Who has influence.

- What are they key processes?

- What areas can you achieve early wins?

- Questions About the Future

- What are the most promising unexploited opportunities? What would need to happen to realize their potential?

- What new capabilities need to be developed or acquired?

- Which elements of the culture should be preserved vs changed?

- Questions about the past.

- You must understand the shadow organization—the informal set of processes and alliances that exist in the shadow of the formal structure and strongly influence how work actually gets done.

- First one-on-ones, ask these questions.

- What are the biggest challenges the organization is facing (or will face in the near future)?

- Why is the organization facing (or going to face) these challenges?

- What are the most promising unexploited opportunities for growth?

- What would need to happen for the organization to exploit the potential of these opportunities?

- If you were me, what would you focus attention on?

- Inboarding, which, as discussed earlier, is roughly 70 percent as difficult as being hired from the outside. In both cases, you likely will enter a different culture and will lack the political wiring you had in your previous role.

Chapter 3: Match strategy to situation

- What kind of change am I being called upon to lead? Only by answering this question will you know how to match your strategy to the situation. What kind of change leader am I?

- STARS is an acronym for five common business situations leaders may find themselves moving into: start-up, turnaround, accelerated growth, realignment, and sustaining success. Launching a venture; getting one back on track; dealing with rapid expansion; reenergizing a once-leading business that’s now facing serious problems; and inheriting an organization that is performing well and then taking it to the next level.

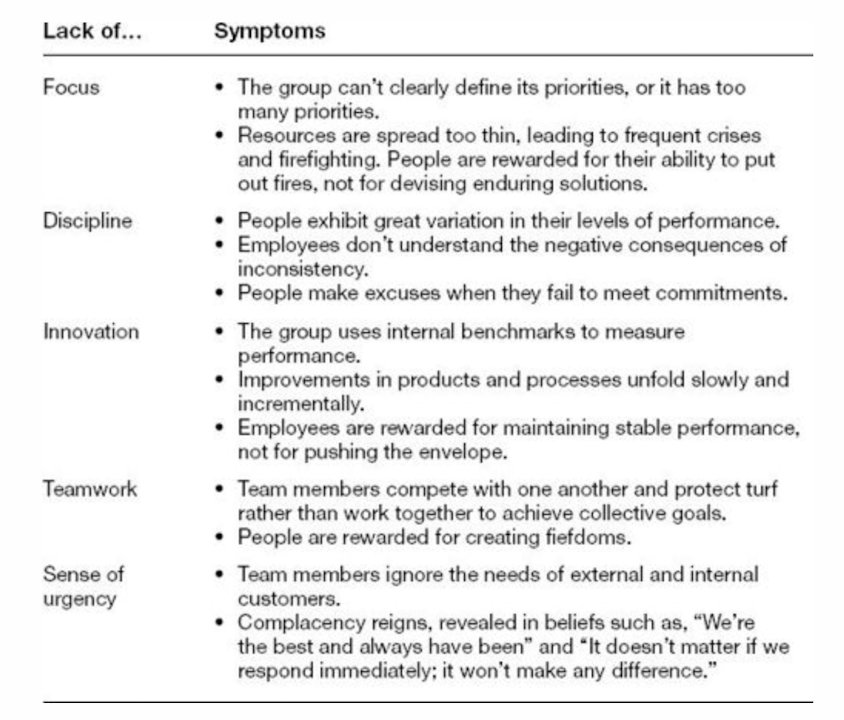

- In start-ups, the prevailing mood is often one of excited confusion, and your job is to channel that energy into productive directions, in part by deciding what not to do. In turnarounds, you may be dealing with a group of people who are close to despair; it is your job to provide them with a concrete plan for moving forward and confidence that it will improve the situation. In accelerated-growth situations, you need to help people understand that the organization needs to be more disciplined and get them to work within defined processes and systems. In realignments, you will likely have to pierce the veil of denial that is preventing people from confronting the need to reinvent the business. Finally, in sustaining-success situations, you must invent the challenge by finding ways to keep people motivated, combat complacency, and find new direction for growth—both organizational and personal.

- In reality, you’re unlikely to encounter a pure and tidy example of a STAR situation.

- You must establish priorities, define strategic intent, identify where you can secure early wins, build the right leadership team, and create supporting alliances.

- You also need to remember that leadership is a team sport.

- Survey: The most challenging situation was assessed to be realignment, followed by sustaining success and turnaround.

Chapter 4: Negotiate success

- Negotiating success means proactively engaging with your new boss to shape the game so that you have a fighting chance of achieving desired goals. Many new leaders just play the game, reactively taking their situation as given—and failing as a result. The alternative is to shape the game by negotiating with your boss to establish realistic expectations, reach consensus, and secure sufficient resources.

- I want to operate on a 90-day time frame, starting with 30 days to get on top of things,” he told her. “Then I will bring you a detailed assessment and plan with goals and actions for the next 60 days.

- Don’t stay away. If you have a boss who doesn’t reach out to you, or with whom you have uncomfortable interactions, you will have to reach out yourself. Otherwise, you risk potentially crippling communication gaps. It may feel good to be given a lot of rope, but resist the urge to take it. Get on your boss’s calendar regularly. Be sure your boss is aware of the issues you face and that you are aware of her expectations, especially whether and how they’re shifting.

- Don’t surprise your boss. It’s no fun bringing your boss bad news. However, most bosses consider it a far greater sin not to report emerging problems early enough. Worst of all is for your boss to learn about a problem from someone else. It’s usually best to give your new boss at least a heads-up as soon as you become aware of a developing problem.

- Don’t approach your boss only with problems. That said, you don’t want to be perceived as bringing nothing but problems for your boss to solve. You also need to have plans for how you will proceed. This emphatically does not mean that you must fashion full-blown solutions: the outlay of time and effort to generate solutions can easily lure you down the rocky road to surprising your boss.

- Don’t run down your checklist. There is a tendency, even for senior leaders, to use meetings with a boss as an opportunity to run through your checklist of what you’ve been doing. Sometimes this is appropriate, but it is rarely what your boss needs or wants to hear. You should assume she wants to focus on the most important things you’re trying to do and how she can help. Don’t go in without at most three things you really need to share or on which you need action.

- Don’t expect your boss to change. You and your new boss may have very different working styles. You may communicate in different ways, motivate in different ways, and prefer different levels of detail in overseeing your direct reports. But it’s your responsibility to adapt to your boss’s style; you need to adapt your approach to work with your boss’s preferences.

- Take 100 percent responsibility for making the relationship work.

- Negotiate time lines for diagnosis and action planning, don’t be pressured to make calls before you’re ready.

- Pursue good marks from those whose opinions your boss respects.

- Your early conversations should focus on situational diagnosis, expectations, and style. As you learn more, you will be ready to negotiate for resources, revisiting your diagnosis of the situation and resetting expectations as necessary. When you feel the relationship is reasonably well established, you can introduce the personal development conversation.

- Whatever your own priorities, pinpoint what your boss cares about most, and aim for early wins in those areas.

- Try to bias yourself somewhat toward underpromising achievements and overdelivering results. This strategy contributes to building credibility.

- Ambiguity about goals and expectations is dangerous.

- “If you want my sales to grow seven percent next year, I need investment of X dollars. If you want ten percent growth, I will need Y dollars.” Going back for more too often is a sure way to lose credibility.

- When serious style differences arise, it’s best to address them directly. Otherwise, you run the risk that your boss will interpret a style difference as disrespect or even incompetence on your part.

- One proven strategy is to focus your early conversations on goals and results instead of how you achieve them. You might simply say that you expect to notice differences in how the two of you approach certain issues or decisions but that you’re committed to achieving the results to which you have both agreed. An assertion of this kind prepares your boss to expect differences. You may have to remind your boss periodically to focus on the results you’re achieving and not on your methods.

- It may also help to judiciously discuss style issues with someone your boss trusts, who can enlighten you about potential issues and solutions before you raise them directly with your boss. If you find the right adviser, he may even help you broach a difficult issue in a nonthreatening manner.

- Don’t make the mistake of trying to address all style issues in a single conversation. Nevertheless, an early dialogue explicitly devoted to style is an excellent place to start. Expect to continue to be attentive to, and adapt to, the boss’s style as your relationship evolves.

- You face even more daunting challenges in managing expectations if you have more than one boss (direct or dotted-line). The same principles hold, but the emphasis shifts. If you have multiple bosses, you must be sure to carefully balance perceived wins and losses among them. If one boss has substantially more power, then it makes sense to bias yourself somewhat in her direction early on, as long as you redress the balance, to the greatest extent possible, later. If you can’t get agreement by working with your bosses one-on-one, you must essentially force them to come to the table together to thrash issues out.

- It is essential to make face-to-face connections early on to begin to establish a basis of confidence and trust (the same is true if you’re leading a virtual team). So if this means you need to fight for the resources and fly halfway around the world, you should do it.

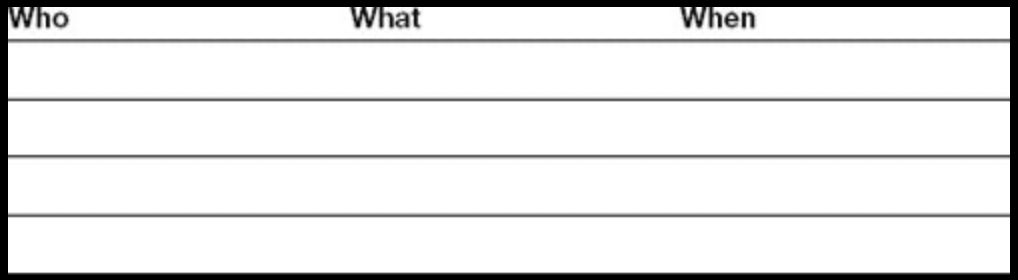

- Your 90-day plan should be written, even if it consists only of bullet points. It should specify priorities and goals as well as milestones.

- Your key outputs at the end of the first 30 days will be a diagnosis of the situation, an identification of key priorities, and a plan for how you will spend the next 30 days.

- At the 60-day mark, your review meeting should focus on assessing your progress toward the goals of your plan for the previous 30 days. You should also discuss what you plan to achieve in the next 30 days (that is, by the end of 90 days). Depending on the situation and your level in the organization, your goals at this juncture might include identifying the resources necessary to pursue major initiatives, fleshing out your initial assessments of strategy and structure, and presenting some early assessments of your team.

Chapter 5: Secure early wins

- By the end of the first few months, you want your boss, your peers, and your subordinates to feel that something new, something good, is happening.

- A seminal study of executives in transition found that they plan and implement change in distinct waves.

- The goal of the first wave of change is to secure early wins.

- The second wave of change typically addresses more fundamental issues of strategy, structure, systems, and skills to reshape the organization; deeper gains in organizational performance are achieved.

- Be careful not to fall into the low-hanging fruit trap. This trap catches leaders when they expend most of their energy seeking early wins that don’t contribute to achieving their longer-term business objectives.

- When you’re deciding where to seek early wins, you may have to forgo some of the low-hanging fruit and reach higher in the tree.

- Define your goals so that you can lead with a distinct end point in mind.

- Work to identify and support behavioral changes.

- So how do you build personal credibility? In part, it’s about marketing yourself effectively, much akin to building equity in a brand. You want people to associate you with attractive capabilities, attitudes, and value.

- Demanding but able to be satisfied.

- Accessible but not too familiar.

- Decisive but judicious. New leaders communicate their capacity to take charge, perhaps by rapidly making some low-consequence decisions, without jumping too quickly into decisions that they aren’t ready to make.

- Focused but flexible.

- Willing to make tough calls but humane. You may have to make tough calls right away, including letting go of marginal performers. Effective new leaders do what needs to be done, but they do it in ways that preserve people’s dignity and that others perceive as fair.

- To nudge your mythology in a positive direction, look for and leverage teachable moments. These are actions—such as the way Elena dealt with recalcitrant supervisors—that clearly display what you’re about; they also model the kinds of behavior you want to encourage.

- They need not be dramatic statements or confrontations. They can be as simple, and as hard, as asking the penetrating question that crystallizes your group’s understanding of a key problem the members are confronting.

- Elevate change agents. Identify the people in your new unit, at all levels, who have the insight, drive, and incentives to advance your agenda.

- Your early-win projects should serve as models of how you want your organization, unit, or group to function in the future.

- Planning Versus Learning

- Plan and implement approach works if you have the following key pillars.

- Awareness. A critical mass of people is aware of the need for change.

- Diagnosis. You know what needs to be changed and why.

- Vision. You have a compelling vision and a solid strategy.

- Plan. You have the expertise to put together a detailed plan.

- Support. You have sufficiently powerful alliances to support implementation.

- If any of these five conditions is not met, however, the pure planning approach to change can get you into trouble.

- You may therefore need to build awareness of the need for change. Or you may need to sharpen the diagnosis of the problem, create a compelling vision and strategy, develop a solid cross-functional implementation plan, or create a coalition in support of change.

- To accomplish any of these goals, you would be well advised to focus on setting up a collective learning process and not on developing and imposing change plans.

- Rather than mount a frontal assault on the organization’s defenses, you should engage in something akin to guerrilla warfare, slowly chipping away at people’s resistance and raising their awareness of the need for change.

- The key, then, is to figure out which parts of the change process can be best addressed through planning, and which are better dealt with through collective learning.

- Plan and implement approach works if you have the following key pillars.

- Simply blowing up the existing culture and starting over is rarely the right answer. People—and organizations—have limits on the change they can absorb all at once. The key is to identify both the good and the bad elements of the existing culture. Elevate and praise the good elements even as you seek to change the bad ones.

Chapter 6: Achieve alignment.

- The higher you climb in organizations, the more you take on the role of organizational architect, creating and aligning the key elements of the organizational system: the strategic direction, structure, core processes, and skill bases that provide the foundation for superior performance.

- Look at how your piece of the puzzle fits (or doesn’t fit) into the bigger picture.

- Think about whether you need to convince influential people—your boss or your peers—that serious misalignments are a key impediment to achieving superior performance.

- Also, keep in mind that a thorough understanding of organizational systems can help you build credibility with people higher in the organization—and demonstrate your potential for more-senior positions.

- The “systems” part highlights the fact that organizational architectures consist of distinct, interacting elements: strategic direction, structure, core processes, and skill bases.

- Strategic direction

- Strategic direction encompasses mission, vision, and strategy. The what, the why and the how.

- Some fundamental questions about strategic direction concern what the organization will do and, critically, what it will not do. Focus on customers, capital, capabilities, and commitments.

- SWOT is arguably the most useful (and certainly the most misunderstood) framework for conducting strategic analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats).

- TOWS is the correct order so that the discussion can become more anchored on the current environment instead of abstract, undirected discussions.

- Suppose you discover serious flaws in the mission, vision, and strategy you have inherited. Can you radically change them or the way they’re implemented? That depends on two factors: the STARS situation you’re entering, and your ability to persuade others and build support for your ideas.

Chapter 7: Build your team.

- Common traps

- Criticizing the previous leadership.

- Keeping the existing team too long.

- Not balancing stability and change.

- Not working on organizational alignment and team development in parallel.

- Not holding on to the good people.

- Undertaking team building before the core is in place.

- It is tempting to launch team-building activities right away, but this approach poses a danger; it strengthens bonds in a group, some of whose members may be leaving.

- So avoid explicit team-building activities until the team you want is largely in place.

- This does not mean, of course, that you should avoid meeting as a group. Just keep the focus on the business.

- Consider these six criteria to evaluate a person:

- Competence and experience.

- Judgment. Does this person exercise good judgment, especially under pressure or when faced with making sacrifices for the greater good?

- Energy. Does this team member bring the right kind of energy to the job, or is she burned out or disengaged?

- Focus. Is this person capable of setting priorities and sticking to them, or prone to riding off in all directions?

- Relationships. Does this individual get along with others on the team and support collective decision making, or is he difficult to work with?

- Trust. Can you trust this person to keep her word and follow through on commitments?

- One way to assess judgment is to work with a person for an extended time and observe whether he is able to (1) make sound predictions and (2) develop good strategies for avoiding problems.

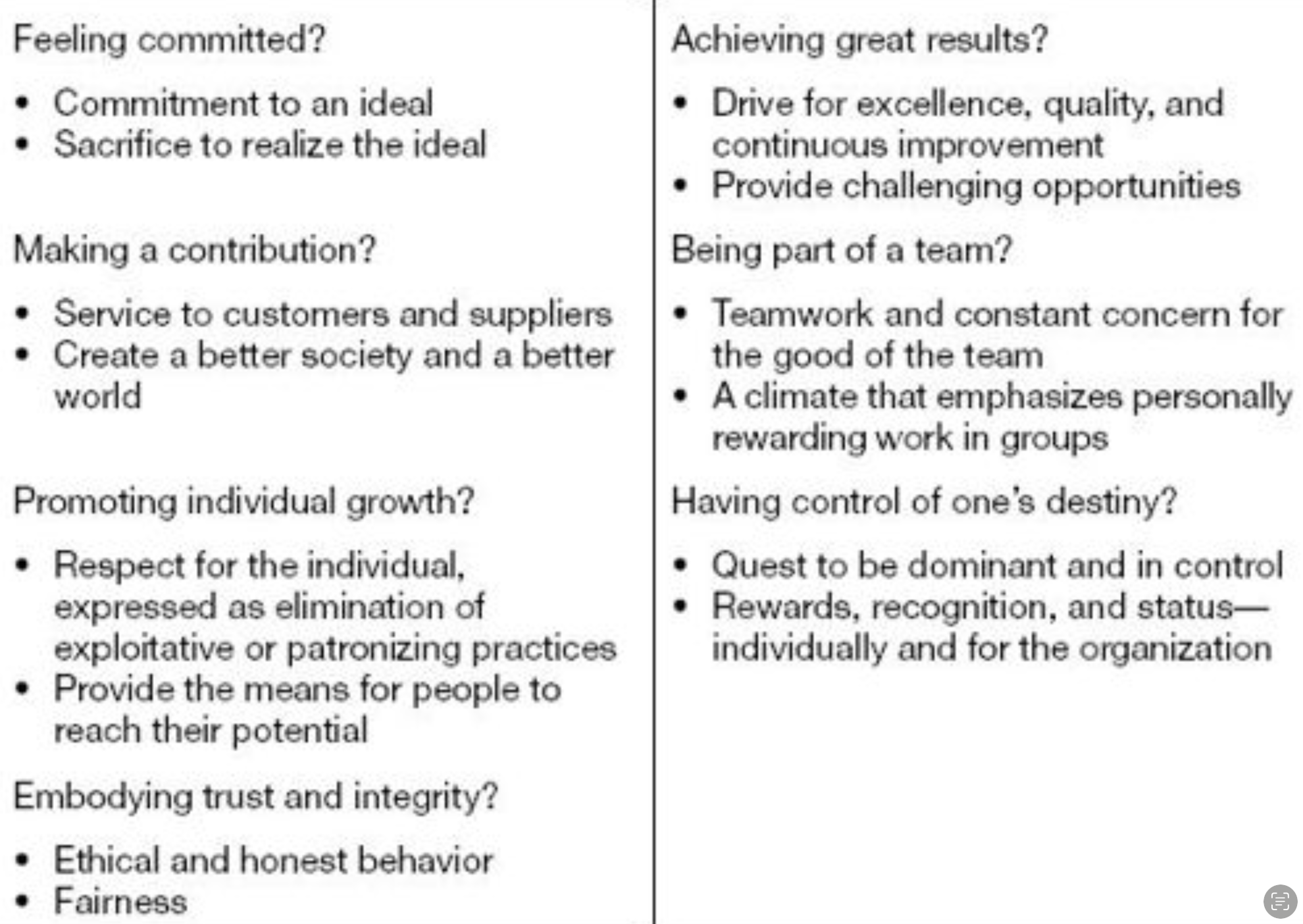

- A blend of push and pull tools works best to align and motivate a team. Push tools, such as goals, performance measurement systems, and incentives, motivate people through authority, loyalty, fear, and expectation of reward for productive work. Pull tools, such as a compelling vision, inspire people by invoking a positive and exciting image of the future.

- mix of push and pull you use will depend on your assessment of how people on your team prefer to be motivated. Your high-energy go-getters may respond more enthusiastically to pull incentives. With more methodical and risk-averse folks, push tools may prove more effective.

- Usually, you will want to create incentives for both individual excellence (when your direct reports undertake independent tasks) and for team excellence (when they undertake interdependent tasks). The correct mix depends on the relative importance of independent and interdependent activity for the overall success of your unit.

- You don’t want to give them incentives to pursue individual goals when true teamwork is necessary, or vice versa.

- An inspiring vision has the following attributes:

- It taps into sources of inspiration.

- It makes people part of “the story.”

- It contains evocative language.

- Off-Site Planning Checklist

- To gain a shared understanding of the business (diagnostic focus)

- To define the vision and create a strategy (strategy focus)

- To change the way the team works together (team-process focus)

- To build or alter relationships in the group (relationship focus)

- To develop a plan and commit to achieving it (planning focus)

- To address conflicts and negotiate agreements (conflict-resolution focus)

- Decision-making processes that most leaders use: consult-and-decide and build consensus.

- In startup and turnarounds, consult-and-decide often works well. The problems tend to be technical (markets, products, technologies) rather than cultural and political. Also, people may be hungry for “strong” leadership, which often is associated with a consult-and-decide style.

- To be effective in realignment and sustaining-success situations, in contrast, leaders often need to deal with strong, intact teams and confront cultural and political issues. These sorts of issues are typically best addressed with the build-consensus approach.

- Especially for virtual teams, don’t forget to celebrate success.

Chapter 8: Create Alliances.

- To succeed in your new role, you will need the support of people over whom you have no direct authority. You may have little or no relationship capital at the outset, especially if you’re onboarding into a new organization. So you will need to invest energy in building new networks. Start early.

- Get your boss to connect you to key stakeholders.

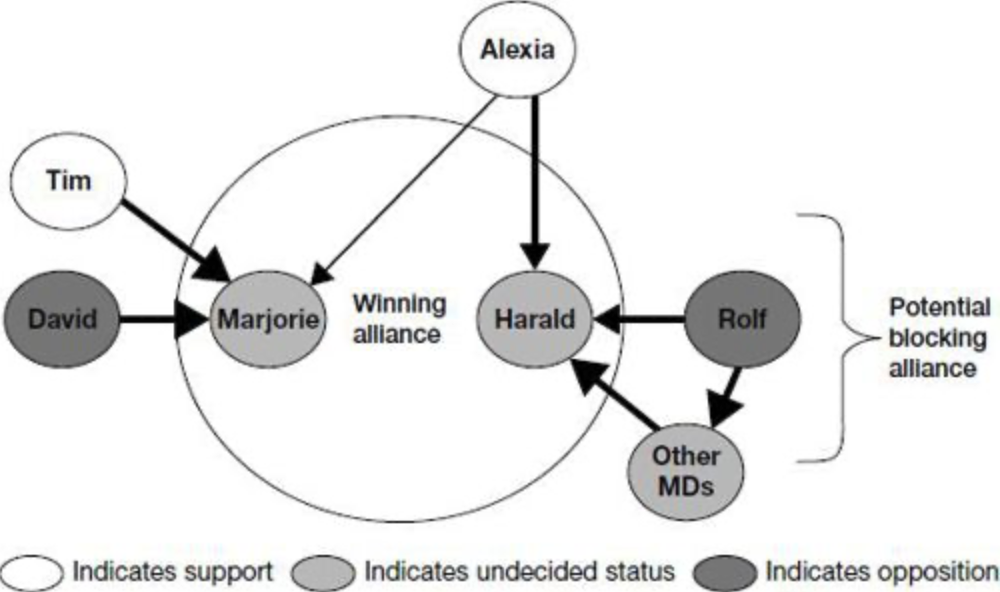

- Steps to create alliances

- First, identify influential players, what you need them to do and when you need them to do it.

- Second, draw influence diagrams.

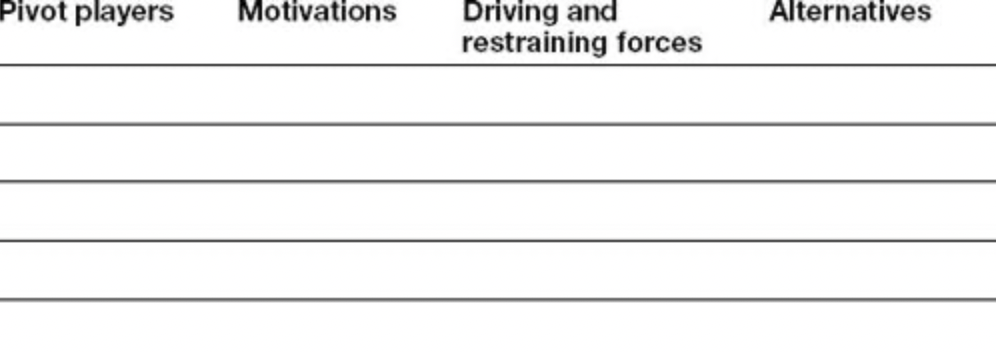

- Third, figure out the motivators, driving and restraining forces and alternatives for pivotal people (detractors).

- Finally frame arguments to convince people.

- Creating Influence diagrams

- To identify your potential supporters, look for the following:

- People who share your vision for the future. If you see a need for change, look for others who have pushed for similar changes in the past.

- People who have been quietly working for change on a small scale.

- People new to the company who have not yet become acculturated to its mode of operation.

- Adversaries may have reasons for resistance to your agenda:

- Comfort with the status quo.

- Fear of looking incompetent.

- Threats to core values.

- Threats to their power.

- Negative consequences for their allies.

- To identify your potential supporters, look for the following:

- Framing arguments

- Consultation promotes buy-in, and good consultation means engaging in active listening. You pose questions and encourage people to voice their real concerns, and then you summarize and feed back what you’ve heard.

- Framing means carefully crafting your persuasive arguments on a person-by-person basis.

- Choice-shaping is about influencing how people perceive their alternatives. Think hard about how to make it hard to say no. Sometimes choices are best posed broadly, at other times more narrowly. If you’re asking someone to support something that could be seen as setting an undesirable precedent, it might best be framed as a highly circumscribed, isolated situation independent of other decisions. Other choices might be better situated within the context of a higher-level set of issues.

- Social influence is the impact of the opinions of others and the rules of the societies in which they live. The knowledge that a highly respected person already supports an initiative alters others’ assessments of its attractiveness. So convincing opinion leaders to make commitments of support and to mobilize their own networks can have a powerful leveraging effect.

- Incrementalism refers to the notion that people can move in desired directions step-by-step when they wouldn’t go in a single leap.

- Because incrementalism can have a powerful impact, it’s essential to influence decision making before momentum builds in the wrong direction. Decision-making processes are like rivers: big decisions draw on preliminary tributary processes that define the problem, identify alternatives, and establish criteria for evaluating costs and benefits.

- Sequencing means being strategic about the order in which you seek to influence people to build momentum in desired directions. If you approach the right people first, you can set in motion a virtuous cycle of alliance building.

Chapter 9: Managing yourself

- It’s common for leaders to go into a valley three to six months after taking a new role. The good news is that you’re virtually certain to come out the other side—as long as you’re applying your 90-day plan, of course.

Dysfunctional behaviors

- Undefended boundaries. If you fail to establish solid boundaries defining what you are willing and not willing to do, the people around you—bosses, peers, and direct reports—will take whatever you have to give. The more you give, the less they will respect you and the more they will ask of you—another vicious cycle.

- Brittleness. The uncertainty inherent in transitions can exacerbate rigidity and defensiveness, especially in new leaders with a high need for control.

- Isolation. To be effective, you must be connected to the people who make action happen and to the subterranean flow of information. It’s surprisingly easy for new leaders to end up isolated, and isolation can creep up on you. It happens because you don’t take the time to make the right connections, perhaps by relying overmuch on a few people or on official information.

- Work avoidance. You will have to make tough calls early in your new job. Perhaps you must make major decisions about the direction of the business based on incomplete information. Or perhaps your personnel decisions will have a profound impact on people’s lives. Consciously or unconsciously, you may choose to delay by burying yourself in other work or fool yourself into believing that the time isn’t ripe to make the call. The result is what leadership thinkers have termed work avoidance: the tendency to avoid taking the bull by the horns, which results in tough problems becoming even tougher.

Three pillars of self-management

- Pillar 1: Adopt 90-Day Strategies

- Prepare yourself: Are you adopting the right mind-set for your new job and letting go of the past?

- Accelerate your learning: Are you figuring out what you need to learn, whom to learn it from, and how to speed up the learning process?

- Match your strategy to the situation: Are you diagnosing the type of transition you face and the implications for what to do and what not to do?

- Negotiate success: Are you building your relationship with your new boss, managing expectations, and marshaling the resources you need?

- Secure early wins: Are you focusing on the vital priorities that will advance your long-term goals and build your short-term momentum?

- Achieve alignment: Are you identifying and fixing frustrating misalignments of strategy, structure, systems, and skills?

- Build your team: Are you assessing, restructuring, and aligning your team to leverage what you’re trying to accomplish?

- Create alliances: Are you building a base of internal and external support for your initiatives so that you’re not pushing rocks uphill?

- Pillar 2: Develop Personal Disciplines

- Plan to Plan. Do you devote time daily and weekly to a plan-work-evaluate cycle? If not, or if you do so irregularly, you need to be more disciplined about planning.

- Focus on the Important.

- Judiciously Defer Commitment. Begin with no; it’s easy to say yes later. It’s difficult (and damaging to your reputation) to say yes and then change your mind.

- Go to the Balcony. Do you find yourself getting too caught up in emotional escalation in difficult situations? If you do, discipline yourself to stand back, take stock from fifty thousand feet, and then make productive interventions.

- Check In with Yourself. Are you as aware as you need to be of your reactions to events during your transition? If not, discipline yourself to engage in structured reflection about your situation.

- Recognize When to Quit. To adapt an old saw, transitions are marathons and not sprints. If you find yourself going over the top of your stress curve more than occasionally, you must discipline yourself to know when to quit.

- Pillar 3: Build your support systems

- Family members’ difficulties can add to your already heavy emotional load, undermining your ability to create value and lengthening the time it takes for you to reach the break-even point. You will need to help them stabilize.

- You need to cultivate three types of advisers: technical advisers, cultural interpreters, and political counselors.

Chapter 10: Accelerate everyone

- Identify number of people who are being hired, getting promoted, moving between units, and making lateral moves.

- Focus on the most important transitions and help support those.

- Before designing a companywide acceleration system, you must first make a thorough assessment of existing systems, as well as identify areas where no support is currently provided.

- Examine the approaches (coaching programs, virtual workshops, self-guided materials) your organization currently uses to deliver transition support at all levels of the leadership pipeline. Evaluate the associated costs and benefits.

- Imagine that every leader in transition were able to converse with bosses, peers, and direct reports about the following:

- The STARS portfolio of challenges they had inherited—the mix of start-up, turnaround, accelerated growth, realignment, or sustaining success—and the associated challenges and opportunities.

- Their technical, cultural, and political learning and the key elements of their learning plan.

- Their progress in the five conversations—situation, expectations, style, resources, and progress—with their boss and direct reports.

- Their agreed-upon priorities and plans for where they will secure early wins.

- The alliances they need to build.