Shape Up - 6 week cycles

Wealthsimple is moving away from 2 week sprints to 6 week cycles. This prompted me to learn more about the Shape Up process which is proposed by Basecamp’s founders (a small sized company).

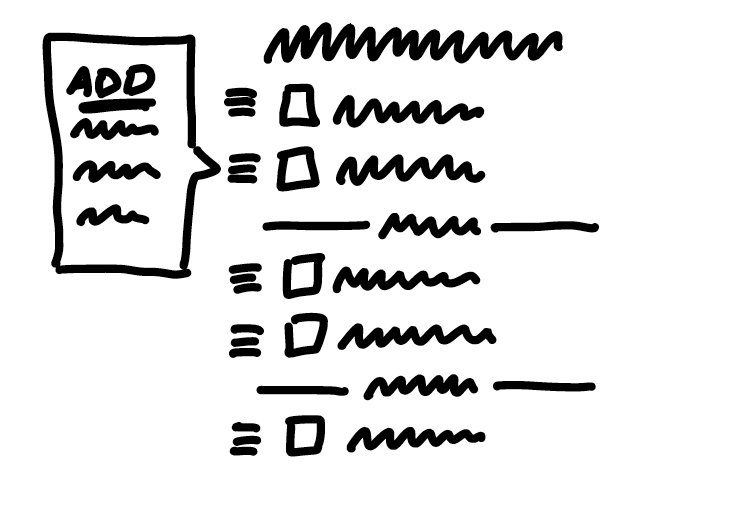

Currently, our process is for a lead (DRI) to work with designers on low-fi mockups (shown below), writing up a tech brief outlining key risks and flows, presenting to technical experts, getting to an MVP playtest as fast as possible, and managing rollout. We have 2 week sprints and the DRI adds tickets for their sub-team. The manager also vets these to find blockers or address risks early. Many of us in the industry are familiar with this approach (“agile”). A chief drawback is captured by the all too familiar question - “how long will this take”?

Projects get delayed because numerous tasks are discovered only when DRIs start implementation. Instead of “how long will this take”, Shape Up provides an alternative- “how much time do we want to spend on this problem”. The DRI has authority to alter scope accordingly. The authors prescribe 6 weeks as the standard time to ship most projects.

The second difference between agile and Shape Up is that there’s a “betting table” process where DRIs pitch their tech briefs to Senior decision makers. Anything that cannot be executed in 6 weeks is discarded and tracked in a decentralized manner. It may be pitched again in the next cycle by a DRI.

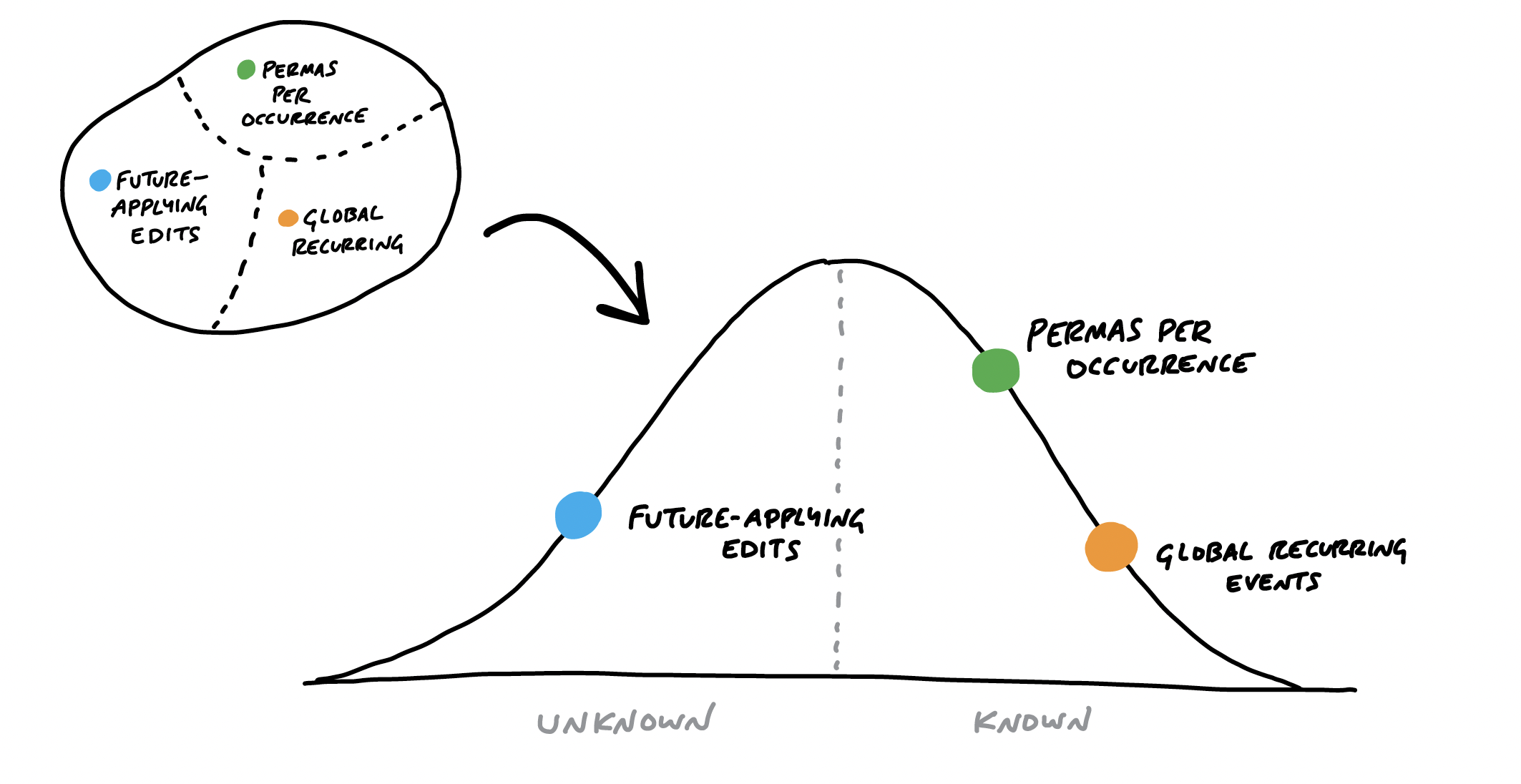

A third difference is that Shape Up doesn’t prescribe the use of JIRA or 2 week sprints, which is a large planning overhead for a manager. Moreover, this maybe seen as micromanagement and talented devs may resent being “ticket takers”. Instead, the DRI creates a scope-map (milestones) for the sub-team and demos the milestones weekly or biweekly. For progress updates, Shape Up suggests a tool called the hill-map. Conveniently, this feature is only available on the Basecamp platform (the same folks who wrote Shape Up). This is what it looks like - dots represent the milestones, and the uphill slope reflects uncertainty while the downhill slope reflects confidence.

The fourth large difference is that 2 weeks of cooldown are scheduled between 6 week cycles. Devs are free to work on tech debt, and the betting table process takes place in these 2 weeks too.

I’m experimenting with 6 week cycles in my team. Having read about the entire Shape Up process, I am pleased to note that we already follow a lot of the best practices. Working on low-fi mockups, writing tech briefs, discussing with experts, frequent demos and pushing for MVP playtest are important. There are some differences e.g., daily standups, sprint planning, JIRA tickets but there are legitimate reasons to continue a few of these. For example, while daily standups can disrupt momentum, they’re useful touchpoints in a remote work environment. Also, Wealthsimple doesn’t use Basecamp so we’re “stuck” with JIRA which is fine as long as we don’t micromanage. Other caveats regarding Shape Up reflect the reality of working in a much larger organization - oncall work, unplanned work, re-orgs, shifting priorities, hiring/firing, performance management, remote work environment, etc. Many of these are contextual so I will scope them out. The authors also note that the process for new product development is different from the regular process (see here).

Important takeaways for me personally were (1) the reversal of the question “how long will this take” to “what can we ship in 6 weeks”, (2) managers should allow DRIs to be flexible with scope - we’ll sign-off but DRIs should be comfortable enough to have these discussions and (3) shipping on time means shipping something imperfect - instead of comparing against the ideal, compare it to the baseline, which is the current reality for customers.

Shape Up - Book Summary

Introduction

- Executing something the wrong way can destroy morale, grind teams down, erode trust, crunch gears and wreck the machinery of long term progress.

- We shape the work before giving it to a team. A small senior group works in parallel to the cycle teams. They define key elements of a solution before the project is ready to bet on. Projects are defined in the right level of abstraction - concrete enough that teams know what to do but abstract enough that they have room to work out the interesting details by themselves.

- Appetite : Instead of “How long will this take”, we ask, “How much time do we want to spend”.

- We give full responsibility to a small team of designers and programmers. This frees up Sr folks to shape up better projects.

- We don’t give a project to a team that still has rabbit holes or tangled interdependencies.

- If a project runs over six weeks, it doesn’t get an extension.

- We integrate design and programming early.

Part one : Shaping.

- Don’t overspecify design - it stifles creativity. Don’t make it too abstract either.

- Properties of shaped work-

- Property 1 : It’s rough.

- Work that’s too fine too early commits everyone to the wrong details.

- Designers and programmers need room to apply their own judgement and expertise when they roll up their sleeves and discover the trade-offs that emerge.

- Property 2 : It’s solved

- Shaped work has been thought through - the main elements of the solution are there at the macro level and connect together.

- Property 3 : It’s bounded.

- It tells the team what not to do. There’s appetite - amount of time the team is allowed to spend on the project. This requires leaving specific things out.

- Who shapes - requires combining interface with tech and business priorities. You need to be a generalist or collaborate with 2 other people.

- Shaping is primarily design work. But you should be able to judge what’s possible, what’s easy and what’s hard.

- You need to be strategic - why does it matter to implement this?

- It’s a closed door, creative process.

- Work on the shaping track is kept private and not shared with wider team until the commitment has been made to bet on it.

- This enables shapers to drop it when it’s not working out.

- Steps to shaping.

- Set boundaries via appetites.

- We set appetite in two sizes (1) Small batch - takes 3 folks 2 weeks, or (2) Big Batch - takes 3 folks 6 weeks.

- If it’s beyond 6 weeks, we have to break the project into pieces.

- Principle is “Fixed time, variable scope”.

- Responding to raw ideas : We should give new ideas space, and say “maybe”. Not “yes” or “no” because we don’t understand it yet.

- Our appetite can also tell us how much research is worthwhile.

- Unclear ideas - the worst offenders are redesigns or refactoring that aren’t driven by a use case. Figure out the definition of done.

- Rough out on wireframes.

- Get the right people in the room (or none).

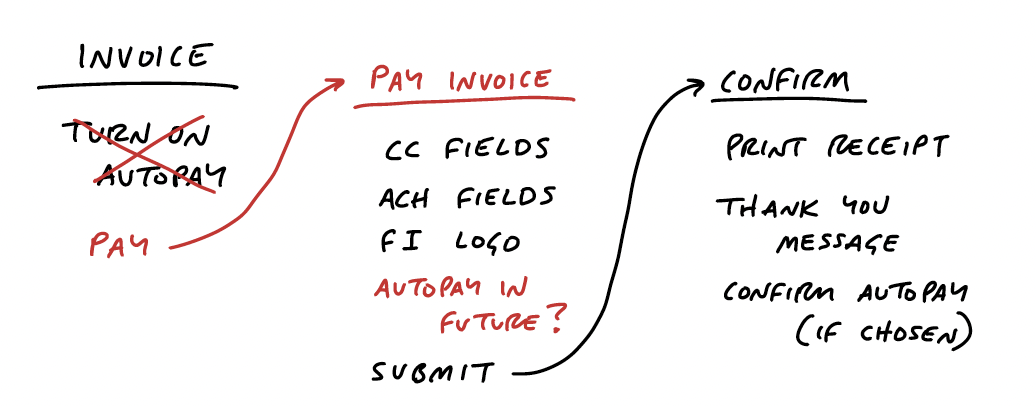

- Breadboarding and fat marker sketches - quickly draw different versions of flows to debate pros and cons.

- Breadboading - only write out (1) places - where users can navigate to (2) affordance - buttons and fields (3) connection lines - how affordance can take the user from place to place.

- Breadboarding uses words to describe the UI flows. But if this isn’t suitable, try fat marker sketches.

- Fat marker sketch is made with such broad strokes that adding detail is difficult or impossible.

- Regardless of what you say, any specific mockups are going to bias what other people do after you—especially if you’re in a higher position than them. This is why fat marker sketches leaves more room for designers to be creative.

- At this stage we can walk away from the project. We haven’t bet on it yet.

- Address risks and rabbit holes.

- Well-shaped work - there’s a slight chance it could take an extra week or two but the elements of the solution are defined enough that it shouldn’t drag any longer.

- In this step, we slow down and look critically - what did we miss? Are we making bad assumptions?

- One way is to walk through a use case in slow motion - how exactly would a user get from the starting point to the end? Slowing down and playing it out can revaeal gaps.

- Specifically call out cases you aren’t supporting to keep the project within the appetite.

- Present to technical experts. The question is not “is it possible”. It is “is it possible within 6 weeks?”

- Write the pitch for betting table.

- There are five ingredients that we always want to include in a pitch:

- Problem.

- Appetite.

- Solution- Show fat marker sketches.

- Rabbit holes.

- No-gos.

- The first step for presenting a pitch is posting the write-up with all the ingredients above somewhere that stakeholders can read it on their own time. This keeps the betting table short and productive. If that isn’t possible in some cases, the pitch is ready to pull up for a quick live sell.

- Set boundaries via appetites.

Part two : Betting.

- At the betting table, we look at pitches from the past 6 weeks or pitches someone revived.

- There’s no giant list of ideas or backlog grooming.

- If we don’t bet on a pitch, we let it go. We don’t need to track it.

- What if the pitch was good but timing wasn’t right? Anyone who wants to advocate for it again tracks it independently.

- We want decentralized lists, no giant backlog.

- Regular 1:1s between departments helps to cross-pollinate ideas for what to do next.

- This approach spreads out responsibility for tracking what to do. This way the conversation is always fresh.

- Important ideas come back.

- We learned that 2 week sprints are too short to get anything meaningful done. And they’re costly due to planning overhead. There’s opportunity cost of breaking everyone’s momentum to regroup.

- People need to feel the deadline looming in order to make tradeoffs. So 6 weeks is appropriate.

- The end of a cycle is worst time to plan because everyone is busy making last-minute decisions to ship.

- During cool-down, programmers and designers are free to work on whatever they want. After working hard of their project, they enjoy having time that’s under their control.

- Betting table is held during cooldown where stakeholders decide what to do in the next cycle.

- The highest people in the company are there. There’s no step two to validate the plan or get approvals.

- Buy-in from the top is essential to making cycles turn properly.

- When you make a bet, you honor it. Don’t allow the team to be interrupted. Losing momentum is really bad.

- If it’s a real crisis, we can hit the brakes, but true crises are very rare.

- Teams have to ship the work within the 6 weeks - if they don’t finish, the project doesn’t get an extension.

- This eliminates the risk of runaway projects.

- If the project doesn’t finish in 6 weeks, it means we did something wrong in the shaping.

- The vast majority of bugs can wait 6 weeks. If we tried to eliminate every bug, we’d never be done.

- Fix bugs during cool down, or bring it to the betting table, or schedule a bug bash (whole cycle to bugs).

- Don’t carry scraps of old work without shaping and considering them as a new potential bet.

- Break the projects down into things that can be shipped in cycle-by-cycle.

- Shape up for new products are different from the regular shape up for building over existing products. There are 3 phases.

- R&D mode

- Our idea is a theory, which means a lot of scrapwork. We can’t reliably shape what we want in advance.

- Instead of betting on a pitch, we bet on the time spent for investigation.

- Instead of delegating to a team, Senior folks form the team. You can’t delegate when don’t know what you want yourself.

- Also the leaders need to be able to judge the long-term effects of design decisions.

- The aim is to spike, not to ship.

- Prod mode

- This is like normal shape up for an existing product.

- Shipping means merging into codebase, but not necessarily releasing to customers. We may want to remove some features.

- Cleanup mode.

- There’s no shaping - the cycle is closer to the bug bash mode.

- Everyone jumps to help wherever they can.

- Leadership makes final cut decisions before launch.

- R&D mode

- Generally we’ll avoid doing design work or discussing technical solutions for longer than a few minutes at the betting table.

- Why a good pitch may still not be done now - Different projects require different expertise. Also, the type of work they wanna do. Availability is another factor.

- Post a kickoff message about the bets.

Part three : Building.

- Don’t assign tasks because everybody gets disconnected pieces. Instead we trust the team to take on the entire project and work within the boundaries of the pitch.

- The team will define their own tasks and approach to the work.

- Talented people don’t like being treated like ticket takers.

- When teams are assigned tasks, each person can execute their piece without feeling responsibility for the project.

- Remember that we’ve done the shaping and set boundaries - now we’re trusting them to implement the pitch outline.

- Allot for QA within cycle.

- The first few days after kickoff is dead silence - teams have to acquiant themselves with code, think through the pitch and find a starting point. Interfering too early hurts the project.

- If the silence doesn’t break after 3 days, it’s reasonable to step in.

- Since the team is given the project and not tasks, they need to come up with tasks themselves.

- The way to figure out tasks is to start doing real work.

- Team should aim to make something demo-able in the first week or so.

- Backend and fronend “affordances” can be coded before pixel perfect screens.

- Visual styling is important in the end product, not early stages.

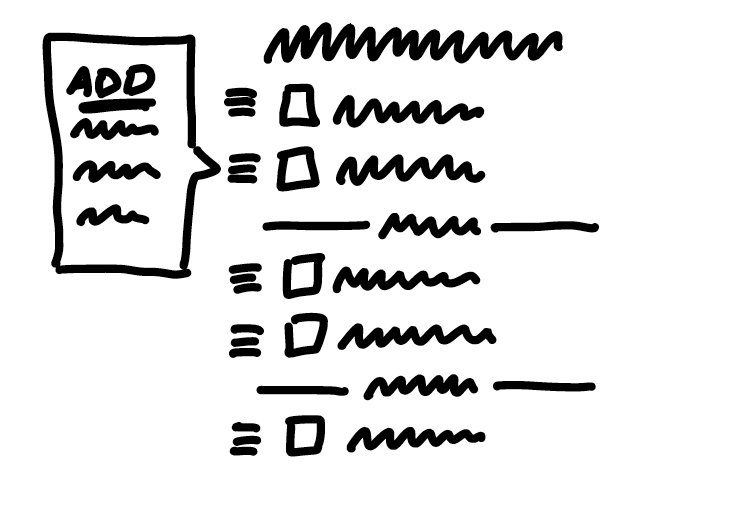

- Create a scope map - break the overall project into multiple deliverables/milestones.

- Well-made scopes show the anatomy of the project.

- Badly made scopes-

- Hard to say how “done” a scope is - this happens when tasks within scope are unrelated.

- The name isn’t unique to a project e.g., “frontend”, “bugs”. This suggests you aren’t integrating enough. Exceptions - iceberg projects where FE is small while BE is very complex.

- It’s too big to finish soon.

- There are always things that don’t fit into a scope - put these in a “chowder” list.

- Separate must-haves from nice-to-haves.

- How to show progress?

- Can’t use tasklist bec. as you implement, new tasks always get discovered.

- Can’t use estimates because some tasks have more unknowns and can be difficult to estimate.

- We use analogy of the “hill”.

- The hill shows how the work feels at different stages. The uphill is full of uncertainty and unknowns while downhill is full of confidence and knowing what to do.

- We can combine scopes with hills.

- The scopes give us the language for the project and the hill describes the status e.g., (“Locate”, “Reply”) and (“uphill”, “downhill”).

- Managers can look at hills when they feel anxious about a project.

- Nobody says “I don’t know”. This causes teams to hide uncertainty and accumulate risk. The hill chart allows everyone to see that someone might be stuck without them saying it.

- Build your way uphill - the first part is “I’ve thought about it”, the second is “I’ve validated my approach” and the final third is “I’m far enough that I don’t believe there are other unknowns”.

- Start the riskier scope first. Sequence the riskiest work first.

- When to stop?

- Shipping on time means shipping something imperfect. There’s always more work than time.

- If we aim for an ideal perfect design, we’ll never get there. But we don’t want to lower standards. Instead of comparing against the ideal, compare it to the baseline - the current reality for customers.

- This should motivate us to make calls on things slowing us down. The 6 week also motivates tradeoffs.

- Scope grows like grass - rather than trying to stop scope from growing, give teams the tools, authority and responsibility to cut it down.

- Cutting down scope is asking ourselves - what makes a difference for the core use cases?

- Code review is about taking advantage of a teaching opportuntiy rather than a step in the process.

- When to extend project?

- Outstanding tasks must be true must-haves.

- Outstanding work must be downhill i.e., no open questions.

- How to try shape up.

- Option 1 : Try one 6 week project.

- Option 2 : Start with shaping.

- Option 3 : Instead of 2 week sprints, work in 6 week cycles.